Roleplaying with Pyramids

© 2007 David Carle Artman & David Mark Cherryholmes, All rights reserved.

Overview

A role-playing game requires, at a minimum, Characters, Situations, a Resolution System, and Rewards for playing. In Stacktors!, the abilities of each player character (PC) are represented by a stack of pyramids. Each pyramid’s position contributes an ability, be it physical, mental, or social. A game group decides what sort of setting—game world, time period, seriousness—in which they wish to play; and then the game master (GM) presents the players with challenges, situations, and story lines in which they can engage. When there is a conflict of interest between characters, a resolution system determines the victor. To the victors go the spoils….

Characters

A character in a game—whether controlled by a player or by the GM—is comprised of a stack of pieces called a character stack, which is positioned on the game map. Similarly, objects—things that the character possesses—are represented by a single equipment stack, which is placed in front of the character’s player.

To indicate a piece’s facing or orientation, character stacks are built on top of a teardrop-shaped piece or paper. Alternately, a small marker may be placed touching the side of the stack which is considered the front face.

The position of a piece and its color determine what ability effect the piece provides to the character. The size of the piece determines its strength, value, or efficacy in such situations.

Piece Positions

A piece can be in one of four general positions in a character stack:

- Brains – (optional) All of the topmost pieces of a stack that are above the neck. Brains typically provide mental or social abilities to the character.

- Neck – (required) A small piece which divides the character’s brains from its guts. Necks do not provide any abilities. A gray neck (i.e. a Volcano Cap) indicates a player character; a black or white neck indicates an enemy or potential ally/burden, respectively.

- Guts – (optional) Any piece which is not feet, brains, or neck. Guts typically provide physical or social abilities to the character.

- Feet – (required) Any and all pieces in a stack which are touching the playing surface. As such, the minimum number of feet is one and the maximum number is three (a full nest). Feet provide movement abilities to the character. Note that equipment stacks do not have feet because there are no feet abilities granted via objects: all pieces below the equipment stack’s neck are guts pieces.

Variation Note: If the playing group has access to a full stash of gray pieces then the GM may choose to use them for Feet objects.

Piece Colors

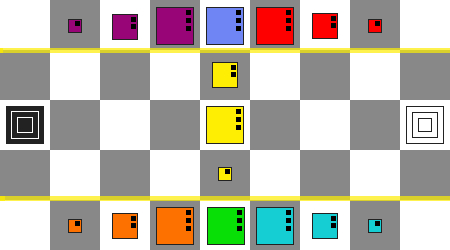

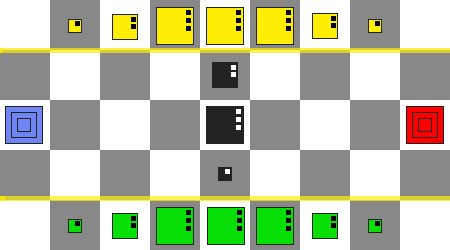

The following table shows the abilities that each piece color provides, for each position in a character stack:

Character Stack Abilities By Position

| Color |

Brain |

Guts |

Feet |

| Clear |

Identify (special)

Claim the piece(s) under a solid piece, once per pip.† |

Perfection (physical)

Attack – Automatically succeed with one attack, before or after resolution (if after, all committed pieces remain committed), once per pip.†

Defend – Ignore one attack, before or after resolution (if after, all committed pieces remain committed), once per pip.† |

Agile (movement)

May move partially, act, and then finish movement.

Note: Do not count clear pieces when calculating total movement points. |

| Red |

Intimidate (social)

Force the defender to flee—move away from the attacker and its allies at its full movement rate—for a number of rounds equal to the pip value of the active red pieces. |

Ranged (physical)

Attack – Attack a defender that is a number of inches away equal to 3 + the pip value of the active red pieces.

Defend – Add the pip value of the red piece to defense against ranged attacks, without committing the red piece. |

Fleet (movement)

Move at double speed (i.e. double movement points), adjusted for the terrain in which beginning movement. |

| Pink |

Shrewd (mental)

Exchange one of the attacker’s pieces with one of the defender’s pieces (attacker’s choice; must be at least one piece from each character), limited to a total pip value equal to or less than the pip count of the active pink pieces. |

Flexible (physical)

Attack – Your current physical attack affects multiple adjacent targets equal to the pip count of the active pink pieces.

Defend – Reflect the attacker’s result back onto it, once per pip per turn (refreshes each turn). Attacker may commit additional pieces to reduce the reflected result to zero (no effect). |

Graceful (movement)

Disengage from enemies without being at risk of a parting shot, once per movement. The number of enemies must be equal to or less than the total pip count of the active pink pieces. |

| Orange |

Persistent (mental)

Immediately re-attempt a just-failed social attack, using the same committed pieces; the defender must commit different pieces to defend against this attack. |

Dexterous (physical)

Attack – Repeat your current physical attack twice, using the same committed pieces; the defender must commit different pieces to defend each attack.

Defend – Defend and counterattack as a free action immediately; the defender and attacker both must commit different pieces for the counterattack. |

Nimble (movement)

Change directions while moving without it costing a movement point. |

| Yellow |

Calming (mental or social)

Force the defender to stop fighting for a number of rounds equal to the pip value of the active yellow pieces. Any attack on the defender during this time period will break the effect and allow it to resume combat on its next turn. |

Medic (special)

Perform healing a number of times equal to the pip value of the active yellow pieces. |

Steady (movement)

Move at normal speed when beginning movement in slowing terrain (e.g. ice, sand), instead of at half speed. |

| Green |

Persuasive (mental or social)

Somehow convince a reluctant potential ally to join the PCs. |

Hamper (physical or social)

Attack – Rather than do normal damage, increase or reduce the pip value of one of the defender’s Feet by one (attacker’s choice), if that is possible with the available unused pieces.

Defend – The attacker immediately reduces the pip value of one of its Feet by one, if that is possible with the available unused pieces. |

Dynamic (movement)

Move at normal speed when beginning movement in cluttered areas (e.g. woods, factory), instead of at half speed. |

| Cyan |

Morph Other (social)

“Heal” the defender 1 pip value, up to a number of inches away equal to the pip value of the active cyan pieces. |

Morph Self (special)

Change the color of one of your pieces whose pip value is equal to or lower than the pip value of the active cyan pieces, if that is possible with the available unused pieces. This ability also commits the affected pieces for this round. |

Fly (movement)Move at normal speed through air, instead of at zero speed. |

| Blue |

Cunning (mental)

Force a defender within a number of inches equal to the pip value of the active blue pieces to commit its pieces first, the next time it is defending against any attack. |

Freeze (physical or social)

Attack – Rather than do damage, force the defender to stay in its location for a number of rounds equal to the pip value of the active blue pieces.

Defend – End the attacker’s turn immediately, even if it still has available actions or movement. |

Swim (movement)

Move at normal speed through water, instead of at quarter speed. |

| Purple |

Compel (mental or social)

Force a defender within a number of inches equal to 3 + the pip value of the active purple pieces to use its next turn to attack the character of your choice, moving into range if necessary (and possible). |

Maneuver (physical)

Attack – Instantly relocate the defender away from its current position a number of inches equal to the pip value of the active purple pieces, without it engaging or being obstructed by terrain, characters, objects, or challenges.

Defend – Instantly move up to a number of inches equal to 3 + the pip value of the active purple pieces, without engaging or being obstructed by terrain, characters, objects, or challenges. |

Teleport (movement)

Instantly move up to full movement points without engaging or being obstructed by terrain, characters, objects, or challenges. If teleporting while engaged, the teleporter may be the subject of an optional parting shot from the adjacent enemy or enemies. |

| Opaque pieces represent either objects—pieces that the player characters may add to their equipment stacks—or NPCs or challenges.

Variation Note: If the playing group has access to a full stash of gray pieces then the GM may choose to use them to indicate objects which provide feet abilities. If so, all players must unground their equipment stack with any available opaque until a feet object grants a feet ability, after which time the object’s piece(s) replace the grounded opaque. Note that you might have to use an extra small opaque to make only the feet pieces grounded; often, however, you can simply rearrange your equipment stack guts pieces to unground any of them that are still grounded when on top of the feet pieces. |

| White |

NPC – If on top of a stack or used for a neck (i.e. a small), White indicates a potential ally. This ally might or might not require persuasion to accompany the players; or it might force itself on the PCs, thereby becoming a burden to protect for an undetermined period of time or until a specific goal is reached.

Object – If on top of completely hidden piece(s), White indicates an unidentified brains ability (or abilities). A character must use the Identify ability to remove the opaque and claim the granted ability (or abilities), which the character may then put into its equipment stack (above that stack’s neck) or give to another character to do so. |

| Black |

NPC – If on top of a character stack or used for a neck (i.e. a small), Black indicates a potential enemy or a challenge (as decided by the GM and the situation). A challenge is further indicated by an opaque foot, called a base, which shows that it is immobile and which distinguishes it from an NPC. Sometimes, the GM may place pieces under the opaque base so that it simultaneously serves as an object reward for surmounting the challenge.

Object – If on top of completely hidden piece(s), Black indicates an unidentified guts ability (or abilities). A character must use the Identify ability to remove the opaque and claim the granted ability (or abilities), which the character may then put into its equipment stack (below that stack’s neck and above its feet, if any) or give to another character. |

| Footnotes:

† = When a “once per pip” ability is used, replace the pyramid with the next smallest pyramid. If it is already a small, remove it from the character stack. Also, such abilities may not be healed, though the character could regain them with additional CP expenditure. |

Character Creation

A given play group will choose one of the following means to create characters, based on the game tone or player preferences:

- Free Creation – Each player get [TBD] character points (CPs) to distribute amongst any number of pieces, to make a character stack. A piece costs a number of CPs equal to its pip value—1 for smalls, 2 for mediums, and 3 for larges.

- Group Creation – Each player gets [TBD] CPs to distribute amongst pieces. Piece purchasing, however, follows a rotation, with each player choosing one piece at a time and paying its CP cost from the player’s total available CPs. This method allows for negotiation between players, to avoid overlapping abilities or to shore up abilities that are lacking for the anticipated challenges.

- Unique Creation – To ensure a really diverse group, with little or no overlap of abilities, the GM might restrict the available pieces to those that come in one Rainbow and Xeno Treehouse stash. Following the above Group Creation method, with only the 24 transparent pieces available in one Rainbow and Xeno stash, will ensure that every character “trumps” the others in at least one ability category.

Character Evolution

Throughout the course of play, situations and challenges won and lost can lead to changes in a character’s total CP or to a character’s stack itself. For instance, a character might lose brains in mental conflict or guts in a social conflict. Likewise, a character might gain a new foot that ungrounds all the other grounded pieces: the new foot grants a (possibly new) movement ability, and all previous feet become guts abilities.

This direct coupling of stack changes to character changes informs most, if not all, of the dramatic outcomes of play. Stacktors! characters can go through significant losses, develop massive sets of talents through advancement, and even die, in the most extreme situations.

Notation Methods

For brevity, a number of notation methods are used to shorten character, challenge, and object descriptions. All notation methods write out a stack from bottom to top, which may seem counterintuitive but is the order in which a stack is built. In addition, various symbols delineate brains, guts, feet, and bases in the stack.

General Notation Guidelines

The color and size of a piece are shown in the following order:

- Color – (C)lear, (R)ed, (O)range, (Y)ellow, (G)reen, (Cy)an, (B)lue, (P)urple, (W)hite, and (Bl)ack

- Size – 1, 2, 3, or x (where x is any arbitrary value; see Challenges).

Character Notation

Follow the general notation guidelines above, putting a hyphen (-) between feet and guts (to make it easier to see how many are grounded) and between guts and brains (to represent the neck). Additional details may or may not be provided in a character description.

Example Soldier – G1O2-R3O2C1-R1

- G1 – Dynamic: All those obstacle courses, all the calisthenics… they pay off.

- O2 – Nimble: All those days marching… they pay off, too.

(feet = 3 MPs)

- R3 – Ranged: Got a big old gun…

- O2 – Dexterous: …and it’s a machine gun.

- C1 – Perfection: Maybe it’s a flak jacket, maybe it’s a grenade—something in his arsenal will save his bacon or drive home damage.

(neck = any)

- R1 – Intimidate: The grunt can be pretty scary to those dumber than he is (which isn’t many folks—but could include most burdens or any character who has already committed all of its brains!)

Challenge Notation

Follow the general notation guidelines above, putting parentheses or braces ({}) around the base (parentheses for white brains object rewards, braces for black guts object rewards) and an equal sign between guts and brains (to emphasize that a character may eliminate either guts or brains to overcome the challenge). Note that, because only the topmost guts or brains color is usually all that matters in a challenge, there is usually only one piece notation followed by any number, which is comprised of any available pieces. Additional details may or may not be provided in a challenge description.

Variation Note: Though none will be presented in these examples, a gray foot object reward is signified by putting double quotes around the base.

Example Locked Chest – (C2)R8=B5

- C2 – Identify (because opaque base is white): A scroll will be found! Note that if this were C1, it would be a break-even proposition, as the object must be Identified, even if part of a challenge. Not much of a reward, then.

(base = white)

(neck = black) Note that the neck will always be black, for a challenge.

- B5: …or a Cunning character can figure out how to pick the lock.

Object Notation

Follow the general notation guidelines above, putting parentheses or braces ({}) around the base (parentheses for white brains objects, braces for black guts objects). Additional details may or may not be provided in an object description.

Variation Note: Though none will be presented in these examples, a gray foot object is signified by putting double quotes around the base.

Example Fine Bow – {R3}

- R3 – Ranged (because opaque base is black): So well strung, it fires up to six inches away!

(base = black)

Turn-Based Resolution

A given conflict is broken up into rounds—a series of turns during which every character has a chance to act.

To determine turn order, each character totals the pip values of its brains or of its feet, ignoring all ability effects (e.g. Fleet). The character with the highest total may go first or pass; if it passes, the next highest character may go first; and the group continues to “count down” in this manner, offering the opportunity to act or pass. Once the character with the lowest total takes its turn—which it is forced to do when its total is reached, or it loses its whole turn—begin to count back up through the totals, offering the opportunity for those who passed to take their turn. If a character passes again on this “count up” stage, it has passed its entire turn away.

On a given character’s turn, that character may do any or all of the following, in any order:

- Move up to its maximum range, determined by the medium or terrain in which the character begins its turn.

- Make one or more actions, determined by the abilities that the character possesses.

- Make a brief statement, usually limited to one sentence.

Movement

A character may move a number of inches equal to the pip value total for all of its feet (including those in its equipment stack, if any). This sum is called the character’s movement points. Note that a small on its side is almost exactly an inch tall; the sides of a large’s base are exactly an inch wide. Many GMs, however, will use battlemats, which typically have a grid of 1″ squares or hexes.

A character must use one movement point to change direction (unless it is Nimble), regardless of the new direction (i.e. a character may turn up to 180 degrees in either direction for one movement point).

A character may not split movement into two stages divided by actions (unless it is Agile); it must move then act or act then move.

Movement Abilities

Every foot color ability effect applies on every movement (including those in the character’s equipment stack, if any).

Example: A character has a large green, a medium red, and a small yellow foot. On its turn, it may move up to 6 inches (3 + 2 + 1) times 2 (because of the red), for a total of 12 inches. Plus, it may move that full value even if it begins its movement in or passes through slowing terrain or cluttered areas (because of the yellow and green).

Terrain Effects

If a character begins movement in terrain, an area, or a medium which reduces movement, it must adjust its total movement points to the fraction of their total, rounding up, as in the following list:

- Slowing terrain (half MPs) – sand, ice, dense underbrush, highly irregular floor, shallow water.

- Cluttered area (half MPs) – forest, factory, ship engine room.

- Water (quarter MPs) – waist-deep or deeper liquid in general; shallow bodies of water are merely slowing.

- Air (zero MPs) – any gaseous medium, presuming gravity is present; if there is no gravity, a gaseous medium is merely slowing.

If a character enters one of the above terrains during its movement, its remaining movement points are immediately adjust by the indicated amount, rounding down. This reduction can result in the character having no remaining movement points.

Encountering Enemies

At any point during a character’s movement, if it becomes adjacent to an enemy—less than 1″ away, or in a neighboring square or hex—then it must immediately stop. It is not required to attack that enemy (and the enemy is not required to attack it), but it is nevertheless considered engaged for the remainder of the round. If the enemy is somehow defeated or relocated before the end of the character’s turn, the character may resume movement, if permitted (i.e. if it is Agile).

An engaged character may move away from an enemy on its next turn, and can move freely around or past that enemy during that turn (i.e. the enemy does not instantly re-engage the character just because it moves into another adjacent position). The enemy, however, may choose to take one action to attack before the character moves away, even if it is not yet the enemy’s turn; this immediate attack is called a parting shot. Also, if an engaged character is moved away from an enemy by another character (i.e. with a Maneuver Attack) then the enemy may make a parting shot. The pieces that the enemy commits to a parting shot are unavailable for the remainder of the round (as is generally true of any committed piece).

Actions

Some actions occur during freeform narration, while others occur during conflict rounds. The guts and brains colors determine what actions a character may take.

Piece Applicability

In most cases—the GM will say when this is not true—a conflict engages only guts or brains.

- Physical conflicts may only use guts.

- Mental conflicts may only use brains.

- Social conflicts may draw on either guts or brains.

A character may draw up pieces from both its character stack and its equipment stack, unless the GM says otherwise.

If there is any question about the applicability of a piece—say, if a recent loss of a piece in the stack changed some guts pieces to feet—then assume that the piece is only applicable based on its current position; ignore earlier positions or the timing of events.

Attacks

If an action targets another character or a thing which has defensive abilities (i.e. it is created with some kind of stack, though that stack may or may not include feet and brains), then that action is called an attack, whether it’s physical, mental, or social:

- The attacker choses which pieces in its character stack are contributing to the total attack value and states which type of attack is being done (i.e. which piece color is active). For the rest of the round, these pieces are committed—they may not be used on follow-up actions or for defense against other characters’ actions.

- The defender then choses which pieces in its character stack are contributing to the total defense value and states which type of defense is being used (i.e. which piece color is active). For the rest of the round, these pieces are committed.

- Neither the attacker nor the defender may activate more than one color per attack.

The total attack value for the action is compared against the total defense value:

- If the attack value is higher than the defense value, the attack succeeds (see Damage, below). If the attack value is a whole number multiple of the defense value, multiply the effect (e.g. a 6 attacking a 2 does triple the effect).

- If the defense value is equal to or higher than the attack value, the attack fails. If the defense value is more than double the attack value, the defending character may immediately counterattack as a free action—it does not cost the defender its action(s) later in the round, nor does it require that the defender not have acted yet this round, though the pieces that the defender uses are committed for the whole round.

Assistance

An adjacent ally or player character (an assistant) may contribute pieces to either character in a conflict—attacker or defender—up to a pip value equal to the sum of all of the assistant’s brains’ pip values. In other words, the “smarter” or more “perceptive” an assistant, the more it can contribute in a given action; as such, NPC burdens typically have few or no brains. For the rest of the round, these pieces are committed.

Note that the contributed pieces need not only be brains (brains total pip values are merely the limiting factor) and the contributing character does not lose the pieces or give them to the acting character; their pip values are merely summed and added to the attacker’s attack value or to the defender’s defense value.

Damage

A successful attack forces the defender to reduce the pip value of one (or more) of its committed piece(s) by one pip value (more than one, if the attack value exceeds the defense value by whole number multiples). If the defender reduces a small piece’s pip value (reducing it to “zero”) then that piece is removed from the defender’s stack and the defender loses its associated ability.

In some cases, the attacker’s active piece will dictate the result, rather than doing damage. If so, do as the piece requires, with the restriction that the total pip value of all pieces in a character’s stack (except its neck) may never exceed the character’s current spent CPs.

Note: Hamper can result in a change of feet and, subsequently, guts.

Healing

Instead of moving or taking any actions, a character may choose to stay in place and heal in one of the following ways:

- Add a small piece to its stack, out of the available unused pieces.

- Upgrade one of its existing pieces to the next largest size, if that is possible with the available unused pieces.

- Downgrade one of its existing pieces to the next smallest size, if that is possible with the available unused pieces. If there is no smaller size (i.e. the piece is already a small) then it is removed from the stack.

A character may not use any of the above healing methods to gain an ability which it did not have at the start of the play session. Note that Morph trumps this rule, allowing character abilities to change.

An ally or another player character may choose to use its movement and all of its actions for its turn to heal an adjacent character. Note that Medic trumps this rule, allowing the assistant to commit only its yellow guts piece(s) to perform healing(s) and leaving all other uncommitted pieces available to perform actions on its turn and move.

The total pip value of all pieces in a character’s stack (except its neck) may never exceed the character’s current spent CPs. Furthermore, these effects may not result in new feet or guts.

Death

Some games might have options for resurrecting dead characters: for instance, allowing another character to heal the character (i.e. add a small guts piece) within a certain number of rounds.

Most games, however, will treat death as final. The character’s player should be allowed to create a new character using starting CPs, spent CPs, or even total accumulated CPs (if the GM feels generous), and that character should be introduced into the story as soon as is possible.

Extra Actions

If, during a turn, an attacker does not commit all of its applicable pieces, it may choose to use its remaining pieces for a follow-up attack. Use the same process as before, with only uncommitted pieces (which become committed when used, as with any action) and only one of their colors being active.

Note that this can result in an attacker possibly getting many attacks in a given turn, in particular if it is able to use Dexterous to double-up each attack. It is entirely possible for a character with three orange guts pieces to get six (or more) attacks in one turn! They might not be very effective attacks, though, if the total pieces committed in each attempt is low.

Special Abilities

Some abilities are marked as special, which means that they do not involve an attack but rather have some other effect.

Unless otherwise noted, the use of a special ability does not use up the character’s actions for a round. The use of a special ability does commit the active pieces, however, as with any action.

Statements

Making a statement can occur whenever the player or GM desires. For verisimilitude, it is recommended that such statements be limited to brief interjections, taunts, or commands; any drawn-out soliloquy or conversation should occur outside of a conflict or should be done as an extended conflict or should be broken up across several turns (the GM will determine which is appropriate for the situation).

Situations

A situation can be anything from trying to bribe one’s way past a guard to a series of combat maneuvers, attacks, defensive attempts, and injuries. The GM presents situations to the players; the players use their character stack abilities, ingenuity, and cooperation to attempt to overcome these challenges. Based on their success or failure, the GM then presents subsequent plot elements, which lead to further challenges; a story may or may not unfold, depending upon the whole playing group’s approach to stringing together these moments of conflict.

In some situations—usually mental, social, or minor in the “grand scheme of things”—the GM will simply narrate the situation and setting and allow the characters fairly free reign as to how they reply and react; timing, granularity of actions, and turn sequences are ignored in favor of conversational flow.

Once things get out of hand—when different GM or player characters are trying to do conflicting actions—then the situation is resolved with the turn-based resolution system.

Discrete Challenges

When the GM creates a challenge, it is represented as a challenge stack with an opaque base to show that it is immobile.

The topmost piece in a challenge stack indicates the color of the ability that a character must use to attack the challenge. If the challenge stack also has a neck, then a character may attack either the brains or the guts of the challenge stack, using the ability indicated by the topmost brains or guts color. Note that this makes the other piece colors in the challenge stack irrelevant, except as they contribute pip values when “defending” (or attacking).

If the attacker commits a sufficient number of pieces to exceed the total brains or total guts of the challenge stack, it does damage equal to the value of the excess committed pieces. Remove that many pips from the challenge stack’s attacked position—brains or guts—saving the topmost of either position for last. A challenge stack’s pieces are never committed during this “defense.”

Sometimes, the GM might choose to allow the challenge stack to make attacks as well, usually immediately after receiving an attack. The GM will often designate the topmost color as active, but he or she may also choose to surprise a defender by using one of the other (now not so irrelevant!) pieces in the stack. The GM will (typically) commit all of a challenge stack’s pieces to such an attack, and it is therefore (typically) only allowed one attack per round. Even if they have been committed to an attack, a challenge stack’s applicable pieces are always counted for “defense.”

When either all of the guts or all of the brains pieces are eliminated, the challenge is surmounted: remove all remaining pieces above its base from the challenge stack. The character that did the last point(s) of “damage” takes possession of any unidentified object reward that the GM might have placed under the opaque base piece.

Abstract Challenges

At times, the GM might want to represent a situation without actually building character and object stacks for everything present in the scene. In these cases, the GM might set up an abstract challenge, representing an entire scene with a single challenge stack.

The GM will inform the players as to how the challenge must be overcome, typically by separating it into stages or a series of discrete challenges. As a particular stage is overcome, the GM removes the top-most piece, revealing the nature of the next challenge in the series (i.e. what color ability must next be used to “attack” it).

Rewards

Success in conflict will usually reap rewards for the PCs.

The GM might provide additional CPs, allowing them to be spent immediately (e.g. “healing” after a combat) or requiring that they be spent at a particular, later time (e.g. “training” to advance an ability).

Similarly, the GM might provide tools, equipment, or other objects that are beneficial to the characters. Such objects, once acquired, are represented by piece stacks in front of the character’s player.

The GM might also provide information—clues, maps, or world facts—that helps the PCs continue in an ongoing quest or overcome some later challenge.

While currency—in-game resources, money, and assets—might also be a reward for success, this puts a burden on the GM to provide a means to spend such currency in a way that is meaningful to the characters. Otherwise, currency becomes a sort of “scoring system” for the players to use to compare against each other (or other groups that encounter the same series of situations).

![]() This work is distributed by David Carle Artman under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License.

This work is distributed by David Carle Artman under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License.

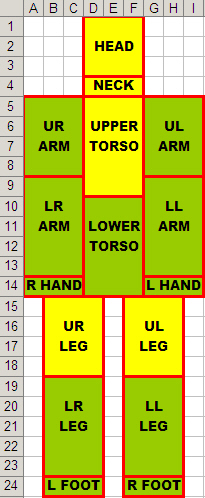

Ebb & Flow uses this chart of valid hit locations and a concept of Action Points (APs) that determine, without randomizers, an attack’s success and effects on the victim:

Ebb & Flow uses this chart of valid hit locations and a concept of Action Points (APs) that determine, without randomizers, an attack’s success and effects on the victim: