a game of addiction, abuse, desperation, and redemption

© Copyright 2008, David Carle Artman. All rights reserved.

Design and Layout – David Carle Artman, david artman designs

The Prime Directive – Meguey Baker, Fair Game

Refinement and Editing – David Walker; Rex Edwards;

“Rustin”; Ben Miller; David Donachie; Dave Michael

It was so simple, at first; so exciting and new. Never a problem, really… you get used to the assholes and the users and all of the downsides; and, man, are the upsides SWEET.

You can handle your shit….

Warning

For Mature Audiences (FMA) is a role playing game designed for adults. It deals with sensitive and taboo topics surrounding depression, sexuality, violence, abuse, addiction, and pain. As such, it is not recommended for persons under the age of 18. Neither the author nor anyone involved with FMA accepts responsibility for outcomes of play, the feelings of players, or resultant fallout. You have been warned. Put the book down now… it’s for the best.

No? Then buckle up. Don’t be afraid, your friends are with you. They care, and they will not abandon you….

The Prime Directive

The Number One rule of FMA is best-summarized by the phrase “I Will Not Abandon You.” Originally coined by Meguey Baker (see sidebar), it is one approach to serious, difficult role playing; its opposite is “Nobody Gets Hurt.” In FMA, you will get hurt. If you don’t feel angst, sadness, frustration, anger, or emotional distress then you have missed the point of play. This game is about finding those touchstones in you, the actual player, and exploring them to reach a deeper understanding of your actual life, through the lens of a fictional one.

But you will not be abandoned by your fellow players. This rule is inviolate, and those players who eschew it should be invited to leave the game. Then forced to do so. You must play FMA with people in front of whom you feel safe to break down, and who will be ready with comfort and understanding when that happens. Even when things become so intense that everyone needs a break for a few moments, no one is left to suffer such a break alone—even during an intermission, you will not be abandoned.

“More Alphabet Soup,” Meguey Baker, 2006

“I will not abandon you” does not equal “nobody gets hurt.”

In “I will not abandon you” (IWNAY) game play, the social agreements are:

- I as a player expect to get my buttons pushed; and I will not abandon you, my fellow players, when that happens. I will remain present and engaged and play through the issue.

- I as a player expect to push buttons; and I will not abandon you, my fellow players, when you react. I will remain present and engaged as you play through the issue.

In “nobody gets hurt” (NGH) game play, the social agreement is that we know where each other’s lines are, and we agree not to cross them.

Both are reciprocal systems. If one person is pushing buttons and the other is supposed to just take it and not respond, then the button pusher is a bully and the relationship is abusive. Notice I’m not talking about the characters, here. This is all about the players at the table. In any game. I bet I could get just as hurt playing White Wolf or GURPS as I could playing Dogs in the Vineyard or Sorcerer.

It sure helps to be clear which kind of social contract is expected: If the players are not all clear, sooner or later you’ll run into a NGH player in a IWNAY game, and they will get hurt, sometimes in a big way. If you get a IWNAY player in a NGH game, that player will wind up transgressing other people’s boundaries and coming off like a jerk. That player may also feel like everyone else is pulling their punches.

Examples:

Good NGH play: Jill has a hard line at kids-in-danger; Robin could make the victim a child, but doesn’t.

Bad NGH play: Jill has a hard line at kids-in-danger, and Robin makes the victim a child anyway. Robin’s obnoxious and Jill may stop playing—Robin has broken NGH.

Good IWNAY play: Jill has a hard line at kids-in-danger. Robin makes the victim a child, maybe even on purpose to push Jill’s buttons. Jill reacts but stays with it, Robin stays engaged, Jill gets to examine something about her issues with kids in danger.

Bad IWNAY play: Jill has a hard line at kids-in-danger. Robin makes the victim a child, maybe even on purpose to push Jill’s buttons. Jill bails out—either by actually leaving the game or by disengaging from it. Jill has broken IWNAY.

Bad IWNAY play: Jill has a hard line at kids-in-danger. Robin makes the victim a child, maybe even on purpose to push Jill’s buttons. Jill reacts but stays with it, but Robin can’t deal with Jill’s reaction, so Robin bails out—either by actually leaving the game or by disengaging from it. Robin has broken IWNAY.

There is a design part to this. When a game has solid support for handling highly intense emotional scenes (which are most-likely to trigger players, I suspect and in my experience), the tendency for the game to require IWNAY play (in order to be successful) is high. Here I think of DitV, Sorcerer, and to some extent Bacchanal. I mean mechanical support for getting into and out of emotionally charged conflict, and solid writing that lets the players understand the reasons why they might allow themselves to be pushed emotionally. This is where the designer gets to say “This can create heavy stuff. I know that. I’m prepared for that. Here’s where I’ve thought about it and how I recommend you handle it my game.” This is the designer saying I will not abandon you; I will give you mechanics to help deal with this when it comes up, I’m with you in this.

Reference: http://www.fairgame-rpgs.com/comment.php?entry=32

As should be obvious, this game is not for casual play with strangers or with passing associates. You won’t be playing FMA at a local gaming convention, unless you can find a very trusting group and a private space. Your fellow players must push you to your limits and beyond… and then be standing there, firm, to hold you up when you begin to fall. In doing so, they will become closer to you than you might ever have expected. Or you might lose them as friends forever, if you or they forget The Prime Directive of FMA.

Do not abandon your fellow players.

What Is Role Playing?

If you have to ask this question, please put this book down and find something more appropriate for your experience level. This advice is for your own protection. Inexperienced role players are far more likely to misconstrue the motives of their fellow players, interpret attacks on their issues as attacks on themselves, or abandon their fellow players when the going gets too tough. Conversely, an experienced role player can balance on the fine line that FMA asks you to walk between self-analysis and character embodiment. You are—and you are not—your character in FMA; and being flexible enough to flip modes when necessary is a learned skill that few possess intuitively.

Overview

The toy box was a calm, quiet place. Sure, the kid would occasionally dig you out and poke and prod and puppeteer you; but that was Before, when you were blissfully unaware, insensate. Then, on a dark night when the kid was at some sleepover… or in Daddy’s bed again… he showed up, bearing blood and the spike and gleeful enmity.

Oh, it hurt, that spike; it seemed to bore into your very soul and pin you like a butterfly removed too soon from the killing jar.

Being alive hurts a hell of a lot more….

[Image no longer available per artist’s request]

The Tooth Dealer, with a ready source of life’s blood for the spike.

In FMA, you take on the role either of the Tooth Dealer (known as a Game Master in other games) or of a Plushie: a character in the story that you will craft with your fellow players, which in the game fiction is a living doll or plush toy. Before you laugh, realize that your new life—or maybe unlife is a better word—is agony. You aren’t the first to awaken, probably won’t be the last. And the others want. They want everything you can give; they want to see you shriek—in joy or pain, no matter—and feed on your new-found, barely controlled emotions.

Basic game play occurs in discrete, sometimes-disconnected scenes; and control over the story and interactions with other characters is almost completely in the hands of the Plushie players. The Tooth Dealer’s primary responsibilities are to ensure that The Prime Directive is enforced and to administer Damage… but you’ll learn about Damage soon enough. More than you’d care to know, in fact.

In general, narrative control rotates around the group in turns; but once a game is well underway, turn order often takes a backseat to the direction in which the group is driving the story. At no time, however, should a Plushie be left out of more than two consecutive scenes—no one should be allowed to get off that easily—and the Tooth Dealer will take control of turn order if such marginalization (or shirking) occurs. In a way, enforcement of turn order is a literal interpretation of The Prime Directive.

The game has several end conditions, or none at all. The choice that the group will make emerges in play. Some groups might find that a handful of scenes is all that they need—or have time for, or can endure—while others might enjoy ongoing play, evolution of characters, and divergent story arcs. As such, FMA has no “final scene” or “climax” that doesn’t come about during actual play. You and your fellow players will know when you’ve had enough….

Beginning Play

Welcome, young one, welcome! Glad you could make it to the Night Party—we’re gonna do it up RIGHT to-NIGHT! Here, let me help you out of that confining coat—who dressed you, the kid? S’alright, s’alright, we’ll get you fixed up good, soon enough.

Soon enough….

FMA differs from other role playing games in that it does not use many of the usual trappings: dice, paper, miniatures, maps. Rather, it takes a very crafty approach—pun intended.

To prepare to play a Plushie character, simply go to a store, a fair, or your sewing room and acquire a plush toy, doll, teddy bear, or similar plaything. You are encouraged to minimize the cost of this Plushie, because game play will likely ruin it as a cute and cuddly familiar… it will become a stark reminder of bad times, if it is not virtually destroyed during play.

The one rule of Plushies is that they must be made primarily of fabric: no plastic or ceramic torsos, limbs, or heads; and no vinyl or leather coverings.

Your choice of Plushie should reflect the general mood that you want for your character… when it is introduced. That mood is doomed, but it should be obvious to all at the start of the game. Often, that mood will contrast the issue or issues that you plan to address; or the basic appearance of the Plushie can symbolize an idealized or archetypal representation of yourself or of your best aspects.

Alice is going to begin play with an innocent, young, girlie doll: delighting in the wonders of life and sensation, happy to help others, quick to trust. Alice buys a perky doll that looks like a cross between Betty Boop and Raggedy Anne.

The only other equipment that Plushie players need to begin play is a pair of unique, disconnected (i.e. not fixed-circular) knitting needles and a bold, permanent marker, like a Sharpie or a Magic Marker. Your knitting needles should be distinguishable from every other player’s needles, so you should favor unusual colors or use patterns of tape bands to make a unique “signature.” The color of the permanent marker is irrelevant, but you might choose a color that matches your Plushie’s eyes or that contrasts your Plushie’s skin or fur color. Getting the picture, yet?

Oh… and odds are good that a couple of handkerchiefs or a box of tissues would not go unused.

The Tooth Dealer has to bring very little to play. It is generally a passive role, until it becomes necessary to enforce the social contract and rules of play. But it is also a creative role, full of opportunities for improvisation and inspiration. The Tooth Dealer at times is called on to take the roles of characters other than the players’ (called “non-Plushie characters;” NPCs) or to reinforce the narration of other players with setting details and background information. As an NPC, the Tooth Dealer is tasked with pushing players’ issues just as much as other players are; and the Tooth Dealer will never abandon—nor allow another player to abandon—any other player.

And the Tooth Dealer has one, key duty to perform, at times. That duty requires a crochet hook. A nice, fat one….

Character Creation

Mmmmm… feel it flow into you. Life! The stuff of Life! So what if it comes from the kid’s sugar-gobbling maw? That’s the Tooth Dealer’s stock-in-trade, after all; he’s handled hundreds of ’em, will handle hundreds more before God or the Devil or whoever holds his soul comes to collect.

No, all you care about is the new rush, your new-found high.

Your lifetime high, as you’ll soon learn….

[Image no longer available per artist’s request]

The Tooth Dealer gleefully injects life into Alice’s dolly.

Once the players have gathered for a game session—ALL players must be present; it’s key to establishing Plushie relationships—the Tooth Dealer will ask each player one or more of the following, intentionally provoking questions:

- What’s your favorite bad or immoral or illegal thing to do?

- What situation will ALWAYS make you resort to violence?

- What group or class of people are you certain are inferior to you?

- When do you revel in others’ pain?

- Whom would you kill without hesitation or reservation?

- What situation would make you take your own life?

- A lifetime supply of…?

You are expected to answer as yourself, the actual person playing, not as some imaginary character. (But see Conclusion, below, for a way to play which could lead you to answer as “just a character.”) The Tooth Dealer should not try to lead you or shape your responses; rather, the Tooth Dealer’s questions should force you to directly address the issue that you most want to confront during play.

After you have answered the Tooth Dealer, he or she will propose your First Scar. A Scar has two parts: the mark and the meaning. The Tooth Dealer will discuss what he or she thinks your Scar means and will propose a way to draw on your Plushie with a marker, to designate the location of the Scar. The Tooth Dealer does not have the final say in this matter; it’s your issue to address, and you may approach it boldly or obliquely, as suits your needs. Thus, feel free to suggest a different First Scar, if the Tooth Dealer asks far too much for starters. But don’t be too much of a pussy about it.

(SIDE) List of examples of Scar marks and meanings, culled from playtester AP reports. (END SIDE)

Alice revealed some personal concerns about addiction and making bad decisions under the influence, and the Tooth Dealer hit upon that as a clear key to introducing Alice’s dolly. He proposes a Scar in the doll’s inner arm—track marks; fat, ugly venous swellings—and the associated meaning of “Junkie.” Alice thinks this is a bit much, and counters with the idea of a heart tattoo on her dolly’s upper arm, with the associated meaning of “Too Easy.” Seeing that Alice seems to want to more-indirectly explore themes of addiction—or maybe just wants to start off a bit more innocent than the average Plushie—he goes with her suggestion. Ultimately, he has no choice in the matter.

Either you or the Tooth Dealer may draw the Scar mark on the Plushie; but at no time should you write down the meaning. It will change, evolve, sicken, or swell over the course of play, even as your mark might change with new Scars adjacent to it. At this point—if you haven’t done so already—you must name your Plushie. Consider your First Scar, your responses to the Tooth Dealer’s prying questions, and your private goals for playing FMA. Some Plushies will start with cutsie, childish names; others will jump right in with ominous names that foreshadow the pain to come.

Alice thinks more about her Plushie’s “Too-Easy” Scar and possibly sex-addled origin, and decides that “Boop” is a perfect name: innocent-seeming exterior belied by a sultry, suggestive personality.

After every Plushie has received its First Scar, the Tooth Dealer will ask each Plushie player to declare his or her First Contact—which other Plushie in the game is the one that he or she first came to know, be it a mere exchange of names or an established relationship? Don’t take things too far, don’t write out some complex intrigues with other Plushies; let those emerge in play. Right now, you are just looking to hook into the “Plushie Community” under the bed, so that you are not floundering for evocative introductory scenes once actual play begins. And besides… betrayal and abuse are right around the corner; no sense entangling yourself too much with these other dysfunctional, pathetic souls.

Beginning Scenes

If they’d JUST leave you alone for a while, you could get a handle on this shit. Just a quiet corner of the toy box, just you and your needle and time to think.

But no, the party never stops, the dances never end, there’s always more to snort or shoot, and they can’t wait until you’re fucked up enough to get your clothes off and… well….

As explained in the Overview, FMA is played as a series of scenes, usually introduced by a Plushie player, in turn order. But it is not a hogde-podge, willy-nilly sequence of establishing location, introducing whomever, and dictating how each participant behaves and reacts. No, this is where the Needles come into play.

To initiate a scene, you must have at least one of your Needles free (at the start of the game both are free, of course; but that might not be the case later in the game). Take that Needle and Spike one of your Scars: literally drive the Needle through your Plushie’s fabric skin or fur, through the Scar mark. This Needle, and the depth to which you drive it, represents how that Scar is driving your actions and reactions in the impending scene. A shallow prick indicates that your Scar is merely suggested in the coming scene, an element of mood or tone hovering over what is to come. A firm Spiking that drives the Needle completely through your Plushie indicates that the Scar is paramount in the scene: the Scar’s meaning is going to be squarely in the foreground, your Plushie probably will be indulging as the scene opens… or fighting not to indulge.

If you have another free Needle, you can introduce another Plushie into the scene in one of three ways:

- You Spike one of its Scars, with similar connotations for that Plushie as if you Spiked your own Scar.

- You Spike an Unscarred spot on the Plushie, which is an attack on that Plushie, intended to Scar it further.

- You ask the Tooth Dealer to invent a character for your use in the scene (an NPC). The Tooth Dealer has exclusive control over the creation and play of the NPC through this scene and future scenes.

Based on how you’ve used your Needles to Spike your or another’s Plushie, you narrate the “opening shot” of the scene, and then you MUST say a line of dialog that the other Plushie simply could not ignore, shrug off, or dismiss. This is called a Volley, and it is the end of scene framing.

Chuck is playing a tough-as-nails teddy bear named Droog whose First Scar is “Sex Deviant.” Chuck Spikes his bear’s groin mark—a cruel-looking, swollen cock—and then leers at April’s Boop and Spikes her Unscared inner arm. As if it’s not obvious enough, he says, “OK, Boop, Droog has just fucked you sideways, upways, and endways. You’re hurting in places you didn’t know a bear could stick his dick. Droog laughs nastily and says, ‘Still like the smack, now that it made you do this?'” Boop is well on her way to a new Scar, probably with the meaning of “Junkie.” “Finally!” thinks the wicked Tooth Dealer, remembering Alice’s diffident First Scar….

[Image no longer available per artist’s request]

The teddy bear Droog has Spiked Boop, but good.

Note that you may open a scene solo, if you don’t or can’t Spike another Plushie. In such a situation, your opening statement could be a brief monologue or a description of your actions, either of which ends scene framing.

Edward is playing an open-hearted, naive sock man named Forrest whose First Scar is “Myopic.” Edward Spikes his sock man through his eye mark—a circle with an X in the middle—and then states, “I’m wandering around under the bed, smiling at folks and waving to Boop when I catch her eye.”

When it is your turn, you must begin a scene, even if you have no free Needles to Spike yourself. In such a situation, the Tooth Dealer must consider the three-way clusterfuck into which you’ve Stuck yourself, and may Spike you with a “virtual Needle” (no knitting needle required, in practice) in an Unscarred location. You won’t like what that means.

At this point, play begins in earnest as the scene is extended, other characters are introduced and exit, and Scarring or Damage—or the ever-rare Healing—occurs.

Extending Scenes

Oh, who have we here? Yes, I remember you… that party last week, right? So, how are things? Uh… sure, OK, I’ll try. What…? But why not here? It’s more fun here. Um… OK, sure, I guess. Lead on….

There is no formal process for playing and extending scenes. The Volley or opening dialog will lead you to your next line of dialog or reaction, which will lead to further exchanges. A scene could play out totally solo; it could be a conflict between two Spiked Plushies; or other Plushies could come and go, possibly choosing to Spike Plushies that are already in the scene, if willing and able. And it ends when it Feels Right… or Far-Too-Wrong.

Introducing Plushies

Should another player want to bring his or her Plushie into a framed scene, the player must have a free Needle and must Spike one of the Plushies that is already in the scene. Note that the player need not Spike his or her own Plushie, because the scene has already begun. However, as with beginning a scene, the player must make a Volley; and its target must respond. This exchange needn’t necessarily be hostile; but the Volley must be something that the target can’t ignore, shrug off, or dismiss.

As Forrest wanders around the party, Boop sees him wave and decides to jump in—it’s an obvious invite by Edward, after all. Alice Spikes Forrest in an Unscarred location—straight through the heart, driven DEEP—and says, “Hey, handsome, why’re you wandering all alone at this wicked party? Come here, let me show you something REALLY wild!” He responds enthusiastically—maybe even a bit lasciviously—and follows her to a pack of cigarettes that the kid stashed under the bed….

[Image no longer available per artist’s request]

Forrest nervously regards Boop’s new-found source of a rush.

Exiting Plushies

Should a player whose Plushie is in a scene want to make an exit, the player need only remove all Needles from his Plushie, returning them to their owners while narrating something that his or her character does or says to extricate itself from the situation. This process is by no means simple, however: each extraction opens the Plushie up to Scarring and Damage.

Forrest doesn’t like the looks of this Boop at all; he’s not ready to jump on the bus to Hell. So Edward extracts Alice’s Needle from Forrest’s heart and says, “Gee, Boop… I don’t think we should mess with stuff like that—it’s scary and you don’t know what it will do to me and I’m not that kind of sock!”

Exiting is primarily a way to bring closure to a scene and let the spotlight move off of your character. It is also, however, a way to back off of a painful situation, to gain some perspective and return stronger… or even Heal. Such a retreat should not be an abandonment of your fellow players; you stay engaged, and you let them stay engaged, and you all prepare to reap the whirlwind later.

Should no Plushie wish to risk an extraction to exit the scene, the scene ends with Stuck Needles (see below).

Scarring and Damaging Plushies

If a player whose Needle is being extracted doesn’t agree with or like the proposed exit, that player may declare a new Scar or Damage on the exiting Plushie. This is often done when someone narrates a retreat from the scene to lick wounds—think of it as a “parting shot.” But it can also be done to a Plushie that makes a “righteous” or “victorious” exit—think of it then as a future threat or a challenge left unresolved.

If the Needle Spiked a previously Unscarred portion of the Plushie then the Needling player may declare a new Scar, subject to the approval of the Tooth Dealer—but not subject to the approval of the Spiked Plushie’s player! The new Scar should extend existing Scars or reflect the player’s answers to the character-creation questions. The Tooth Dealer’s role as approver ensures that new Scar don’t come out of left field, forcing the player to deal with “issues” that they don’t really have and, thus, could not engage.

Alice isn’t letting Edward off that easily; she’s Spiked Forrest’s heart for a very good—no, not good; rather, a very CALCULATING—reason. She says, “Oh, no, Forrest, sweet boy. You aren’t walking away from my offer… my OFFERS… that easily.” And then Alice proposes that Forrest’s next Scar be Boop’s name, over his heart, with the meaning of “Infatuated.” The Tooth Dealer loves the idea; and Edward breaks out his marker, muttering under his breath.

Conversely, if the Needle Spiked an existing Scar then Damage is the inevitable result, and the Tooth Dealer gets out his Hook. Though the Tooth Dealer is the instrument (or, rather, his Hook is) it is always the case that the Plushie that is doing the Damage is to blame for the results.

The goal of the Tooth Dealer is to viciously drive the Hook into the Needled Scar and yank out as much Plushie stuffing as is possible with one pull. No matter which Plushie, no matter who did the Spiking: the Tooth Dealer is getting his payback for the life granted to the Plushies… and payback’s a bitch.

Because of the imprecision of the Hook, however, the stuffing ripped out could be just a bit of fluff, or it could wither a Plushie’s entire limb… or head. The player of the Damaged Plushie must narrate what this Damage means, as appropriate to the scene progression and the manner in which he or she tried to exit. No two instances of Damage will be alike, except in the way in which they rend and deform the Plushie. And as should be obvious, there’s no provision for re-stuffing a withered Plushie—life is hard, suffering leaves its mark, and all that we can be sure of in life… or unlife… is death.

Droog hasn’t taken a shine to Forrest since Forrest’s been seen ogling and wandering off with his new-found squeeze, Boop. Chuck frames a scene in which Droog Spikes the very Scar that Boop left on Forrest’s heart—a lovely, cursive “Boop” across his chest—and drags him into a violent scene of confrontation, threats, and verbal abuse. Forrest doesn’t go in for this sort of treatment one bit, and he extracts Chuck’s Needle from his Scar while declaring that he is stomping off in a huff, ignoring the brusque bear. “Nu-uh, nancy boy!” crows Droog, “You might love Boop, but I fuck her on the regular, now that she loves the juice more than herself… or YOU!” and he looks archly at the Tooth Dealer. With a slight shake of his head—impressed or chagrined, no one can say—the Tooth Dealer takes out his Hook, reaches quietly for Forrest… and literally tears his heart out.

[Image no longer available per artist’s request]

Forrest didn’t know what he was getting into with Droog until it was too late.

It is important to note that Forrest could have counter-Spiked Droog during that scene, to spread around the pain of exiting (if Edward had a free Needle). Perhaps Edward could have leveraged Droog’s “Sex Deviant” Scar to narrate an accusation that Droog can only control Boop with drugs, not with his presumed sexual prowess. Then, when he exits the scene, Droog is left to deal with that Spike until he attempts an exit; or he may leave it Stuck, to do its damage in a later scene.

So now that you’re ripped up a bit, you want out, right? If the Plushie who started a scene exits, its player may extract his or her own Needle with no penalties. You’re used to your habits; only others can make them hurt….

Stuck Needles

A scene usually doesn’t end until all Needles from other players are extracted from all Plushies in the scene. Yes, this means that Scars and Damage are almost guaranteed with each scene—it’s a nasty world full of broken toys.

However, if a scene simply must end at a certain point, because all participants feel it’s well-rounded or has reached a clear conclusion without commensurate extractions, then the Needles are Stuck. Any future scenes that begin with or introduce a Plushie with Stuck Needles will automatically begin with or introduce the Plushies of those players who own the Needles. In a sense, the previous, unresolved scene has forged a bond or a persistent relationship (or a grudge) between the Plushies; and only through a painful extraction will they be free to move alone in the world.

Healing

Like a new dawn, a spring rain… all your thoughts clear of pain… however did you live that life… whyever did you face such strife…?

Not every scene in FMA results in Scars, Damage, and tattered Plushies. It is possible that, through the course of narration and dialog, an epiphany can occur or a long-hidden pain can be exposed and purged.

A player may ask that a given Scar be Healed, if the scene progression or story-arc resolution warrants it. The player must make a formal, out-of-scene proposal to the Tooth Dealer and to the other players. Only though a unanimous decision by all players can a Scar be Healed—your fellow players aren’t there to make the game “easy” or “light;” and yet they will not abandon you, when you truly believe that it’s time that you grew. Never forget that FMA is primarily about guided self-healing. The group MUST recognize the real, actual player epiphany to approve of Healing—this is when they reinforce the personal insights that brought you to this point in play… and in your life.

In game-play terms, a Scar is Healed when the group ratifies the proposal. For ongoing play with the same Plushie, you must patch over the Healed Scar in some manner, be it an iron-on decal or a sewn-on patch or even a patch that perfectly matches your Plushie’s skin or fur. You may not, however, re-stuff your Plushie when patching over a Healed Scar; you can never completely Heal the Damage done, and you probably wouldn’t want to do so anyway—what if you forget and fall back down the rabbit hole?

Check that fucker out: Droog the bear has been played a time or two before the session shown in the artwork above; one might wonder what horrors he has Healed in the past, that he is nevertheless still such a vicious bastard….

Conclusion

You made it… this time. Next time, who knows? The Needles always make new marks; there’s always another monster under the bed; you’re never really safe enough to turn your back on the darkness. Sit back and smoke your last cigarette….

FMA is not a “fun” game, though it can be rewarding. Neither is it a “light” game, if played to the hilt; it is supposed to push you, the player, further than you are willing to go and then bring you back, shaken but not broken, to more-solid ground. If you want it to do so, FMA can put a mirror before your heart and soul and show you things about which you may not want to know, but of which you are best not left ignorant.

That’s not to say, however, that FMA can never be a light, fun game full of humor… albeit dark humor. The group’s choice of Plushies and starting Scars can lighten the mood considerably, sending signals to each other that this game or session is going to be less gut-wrenching. It is best to discuss such a change of tack with the group prior to play; otherwise, a real-life conflict can ensue as you find yourself playing at cross-purposes. Yet, even such “incoherent” play can be successful and rewarding, if you always follow The Prime Directive—even if you are playing “just a character,” it is very likely that another player will push you when you weren’t expecting it. Take it, stay engaged, learn something about yourself… and then push right back! After all, that bastard’s playing “just a character,” too, right?

Be safe, play unsafe, and do not abandon each other.

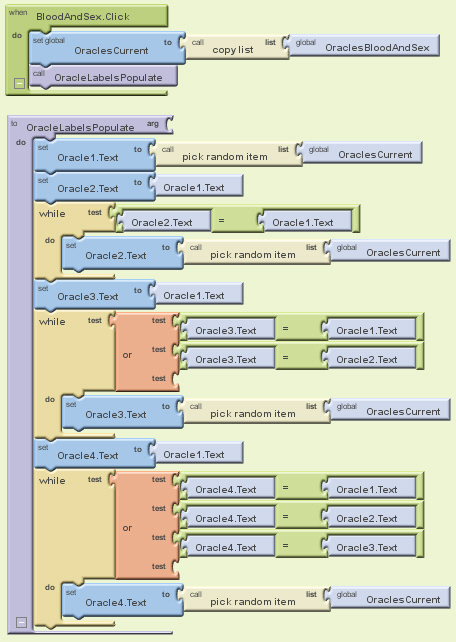

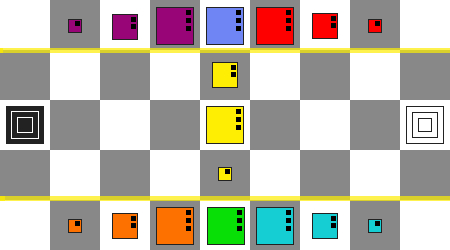

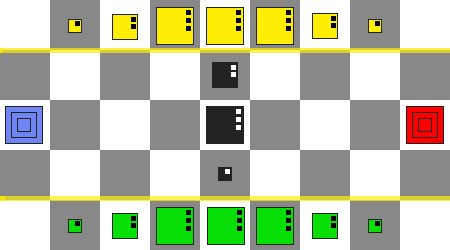

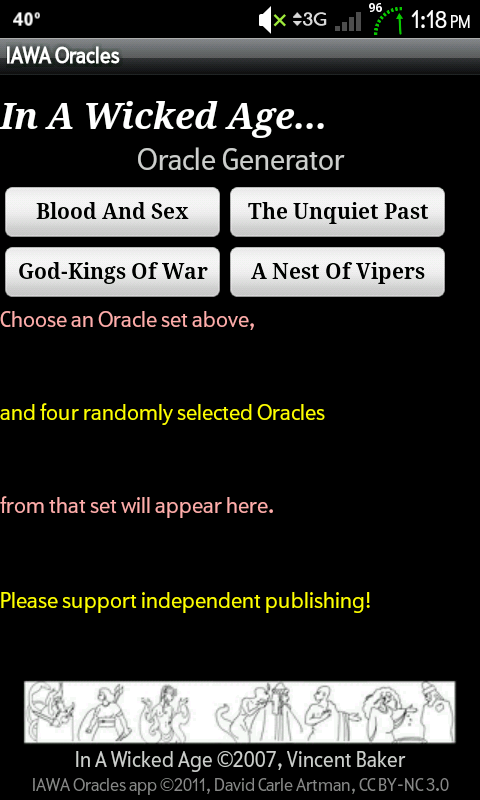

I decided to try out Google App Inventor, being invited to the Beta. I wanted a simple enough project to get a feel for the process without becoming bogged down in complex logic or user interface (UI) design. It occurred to me that a random Oracle generator for the In A Wicked Age role-playing game by Vincent Baker would be interesting enough and maybe even useful to others.

I decided to try out Google App Inventor, being invited to the Beta. I wanted a simple enough project to get a feel for the process without becoming bogged down in complex logic or user interface (UI) design. It occurred to me that a random Oracle generator for the In A Wicked Age role-playing game by Vincent Baker would be interesting enough and maybe even useful to others.