From a post at Story-Games.com

David Artman Jan 7th 2009 edited

First, thanks for backing off terms… so let’s back off “what is art” as that’s never been answered by even Rhodes Scholars. 😉

Posted By: TomasHVM– And let us discuss how the games-format may influence the reading.

- What kind of qualities are present in a game-text, and in the reading of it, that makes it a strong communication device?

- How can we make really readable game-texts?

NOW, we’re cooking with gas: something we can attempt to enumerate, techniques of writing and what they accomplish. *puts on dusty old Lit Crit hat and robes*

OK, one thing RPG manuals tend to have is a structure which is influenced by the procedural nature of play: when do you do what and why and what’s next? Other than technical manuals (in all their forms, from “How To” books to IT manuals), no other “genre” of writing does that. What does that buy us? I’d say it brings a sort of formalism and pacing: aside from authorial voice and varied diction, they are going to give a sort of “march” feel to the work. Maybe even meditative, as the pace is felt and matched by the reader.

They also tend to present information in referential manners, be they summaries of procedures, or just your typical charts and graphs of laundry lists of shit. This referential format strips out every nuance, dictional curlicue, and “voice” to present the bare facts. In that way, they can be like the “HALT!” shouted by a drill sergeant, to continue to (ab)use my marching metaphor–the cadence breaks as we rattle off a list of terms or numbers or both, like presenting arms. Compare that to, say, those statistics list one reads that convey a message, e.g. (stats not real, but close):

* Billions spent on heart disease research in 2007: 45

* Number of American death from heart disease in 2007: 500,000

* Billions spent fighting terrorism in 2007: 300

* Number of American deaths from terrorism in 2007: 16

The point is made crystal clear (above: our government spending priorities are FUCKED), but with nary a jot of expression or style. Editorialized by the timing and choice of what is listed, not by the tone or mood conveyed in the writing of the list.

I’ll stop there, for now, to see if I’m spring-boarding the right way (or hieing off into the trees). For obvious reason, I won’t bother to address “game fiction” or “setting fiction” at this point, as it uses all the same devices of a novel or short story, and that’s of minimal interest to me (mainly because there’s already a HUGE body of work that addresses how to do those forms). Readability, I’d say, falls into the same camp: a readable game text has the same qualities as a readable magazine article, novel, or biography. Clarity, diction, etc (or the opposite, if you’re going all deconstructive on us). Become a decent writer–poetry, prose, manuals, whatever–and you will be a good game writer.

– And measured against “ordinary” literature:

- Is it possible that a games-format is a stronger read than say; a novel, in certain aspects?

- Could a book of game-texts be as good a read as any collection of short stories?

Stronger? hard to say–what’s the point, what’s the theme, what’s the message? Every format suits some deliveries more than others. I want to woo a woman, a poem is going to go better than an 800-page novel. I want to explore a nuanced and complex theme, through the agency of several interrelated characters? I’m at the least going novella.

As for the second question, I’m going to go cheap and just say, “Sure.” Particularly with game text of the type you’re most suggesting: the RPG Poems With A Message. Time and tastes play a big part in that, though: a book of fan fic shorts about Star Wars will probably bore me FAR more than some witty, thought-provoking, or saddening RPG Poems that hit me square between the eyes with issues current and near and dear to me.

So, really, the better (or more interesting to me) question is what things can RPG Poems do BETTER than existing formats; and I believe I begin to explore that above, by unpacking a bit what an RPG format is and what that does to the reader’s expectations and reading behavior. And, as I said above, I’d like to be sure we want to go there before I do that heavy lifting–being a game writer AND editor AND technical writer, I can go into a fair bit of depth about atonality, neutral (AKA common) diction, procedural presentation and structure, projecting attitudes, and “writing between the lines.” Hell, you’d be amazed at the sort of shit a Major Corporation has me do, to “write around” flaws of design without admitting them–that’s, basically, the exact tack, flipped, that Somalian Children takes.

(Sorry so long, but that’s what you get for intriguing me.)

[edited for clarity and corrections]

TomasHVM Jan 7th 2009 edited

This is really good: This referential format strips out every nuance, dictional curlicue, and “voice” to present the bare facts. I see what you are aiming at here, and it tingles my brain! I would very much like to read your thoughts on atonality, neutral diction, procedural presentation and structure, projecting attitudes, and “writing between the lines.” ALL of it, and more, if you would … please!

David Artman Jan 8th 2009

Baseline writing and what’s left unsaid

So I’m going to write a “LitRPG” (I need a shorthand). I can approach it like Somalian Children, with an essentially neutral tone–no rants, reads like a tech manual–and let its very starkness carry my meaning. Here’s a chart, roll your d10s, consult the chart to see your fate. BUT, if you know anything about math, you see that you’ve got a 1:1000 chance of surviving–that’s not said in the text, that’s left for you to realize. And the realization of the unsaid carries the message and theme and impact. Now you can re-read and the whole tone is changed; the cynicism just drips off the page. HOW? The text hasn’t changed. The tone is still there, sill consistent and neutral. But now, having “got it,” you can imagine the author staring balefully at you, accusingly, his voice so flat he sounds like the dead. Becasue isn’t that the REAL point: what have YOU done to help these poor children? Isn’t that the takeaway message, the unsaid?

Projecting attitude

That neutral tone, however, needn’t be the whole bag… in fact, more and more “RPG texts” are conveying a strong authorial diction and style, moving away from (and even mocking) the neutral tone of a tech manual. So our LitRPG can take that tack, and present a seeming “game,” but with an editorialized voice that shows it’s clearly not meant to be played and, rather, is meant to carry a message or cause a change of thought. I’ll bring up HoL, here, as an easy and obvious example of this (IMO). Yeah, sure, the game is somewhat playable, with a lot of rule repair and addition (or a freeform-loving play group), but it’s REALLY suppose to be a screed. It’s a punk zine disguised as a game which (it seems) takes the piss out of all the “structure” of gaming–could they be one of the first “system doesn’t matter” writers? Are they trying to say, “look, just have fun and fuck the details,” or are they actually MOCKING those gamers or that gaming culture which get so buried in stat and crunch that they get twenty minutes of WOW for every four hours of play? (Sound familiar? HoL authors as first Forrgites?!?) Or am I bringing my own experiences into the mix; am *I* the one projecting meaning and attitude onto the book? For the record, I’d say no in this case: I read HoL when it came out, WAY before exposure to all this theory, and I still saw it as taking the piss out of many contemporary RPG systems. But another LitRPG could well work with ambiguity, leaving each reader to project onto it their own interpretation and intent, just as much poetry does.

Atonality

So above we have the two poles of a tonal continuum: writing between the lines and bitch-slapping with editorializing. But there’s a third path, an orthogonal axis: one can use shifts in tone in a LitRPG to really hammer a point. If I have you lulled into the meditative march of neutral tone procedural writing and then, WHAM, start off on a screed about how this fucking chart is WORTHLESS if you don’t have a heart to care about the children, you fucking DICK!

Well, you sort of snap to attention, no? Where did all THAT come from, what did I just miss? Is this guy schitzo? Etcetera. You, as a reader, have to engage different mental gears to address this shift in tone… and then engage still more when I drop back into a staid and steady, neutral tone again. Done poorly, this atonality will seem like Tourette’s Syndrome (just as bad atonal music sounds like folks in different rooms, tuning up or adjusting their synthesizers). Done properly, it can underscore the moments of consistency AND convey a message, via contrasting tone, with the moments of insanity (just as the completion of an atonal music progression can make all the disjointed notes attain a sort of “metaharmony”).

Structure

This one is the big one, because for all the talk of tone, it’s the order of presentation which carries at least half the weight. In a typical RPG, we often see a color piece, to establish the mood of play for the game, followed quickly by a series of definitional sections, so that one isn’t totally lost as to what to do when the procedural stuff starts using the game jargon. Suppose that was tossed out the door? Suppose an RPG was written like A Clockwork Orange, with immediate total immersion in a nearly thoroughly different language? What is said, by that? One has to read it twice, just to get the sense–or jump to the glossary in the back of some editions, to try to get a baseline. A LitRPG can do the same thing, by eschewing the standard structure of a typical RPG.

But what is said by FOLLOWING the typical RPG structure: intro, define terms, establish character, present procedures of play, flesh out setting (again, fiction or reference material or monster lists or whatever). That goes back to tone and diction: is it homage or satire? Or is the fact that it’s hard to answer that question part of the exploration of the LitRPG?

Or, rather than eliminating common structure or following it to convey additional meaning, what about a disjointed structure? Cart before the horse stuff–all the procedures of play presented before you even know if you are a character or in author stance or what; absolutely no information about setting in the presentation of what is clearly NOT a generic system? Can a LtRPG carry surprises, nestled in the sequence of presentation, just like a novel can use flashback to clarify what was, prior to the flash, a very ambiguous or downright confusing scene? What is meant when such structure conventions are violated? A whole branch of “LitRPG Theory” can grow out of just the considerations of structure and how it informs the piece, just has been done with conventional (and, moreso, experimental) literature.

David Artman Jan 8th 2009

Anyhow, just another nudge–that’s why it’s mostly questions and not a list of rules. There’s more LitCrit tools we can bring to bear, as either measures of a LitRPG’s merits or as guides to creating an effective one (I prefer the latter, but that’s also the only reason I studied LitCrit: to be a better writer, NOT a good critic).

David Artman Jan 8th 2009

We game designers use atonality all the time, but it’s to reinforce STRUCTURE, not theme or intent.

There is the cold and clear, neutral tone of a process or rule statement, highlighting its importance or canonical nature.

Then you get the more authorial and looser sort of writing which is, like, in sidebars or advice chunks or those little “talking head’ icons folks use to say, “Hey, now I’m just talking to you, to let you know what’s going on under the hood here.”

And, yeah verily, there be in-fiction tones that put thee into a mind to portray the shining heroes and scurrilous villains in a way which is meet.

See there? Three tones, each with a functional role in the text, but none of which is intended to layer on nuance of the overall book’s INTENT… because it’s only real “intent” is to teach you to play a game the way the author envisioned it. EVEN IF proper gameplay enables the underlying intent of a game to educate or inspire (think Grey Ranks, here).

But using atonality in a LitRPG would (should? could?) drive at the message, at the theme, at the takeaway of reading the text itself, without ever engaging in whatever “rules” or “procedures” are presented as carriers for that message.

OK, ’nuff for now. Your volley….

TomasHVM Jan 8th 2009 edited

Posted By: David Artmanyou’ve got a 1:1000 chance of surviving–that’s not said in the text, that’s left for you to realize. And the realization of the unsaid carries the message and theme and impact.

Clear point, and very good!

I love the idea of readers discovering such content in the text, due to the instructive format. to have a table convey the central point, like in Somalian Children, is something I find very intriguing.

Projecting attitude

Posted By: David Artmanan editorialized voice that shows it’s clearly not meant to be played and, rather, is meant to carry a message or cause a change of thought.

An alternative, yes. Texts with attitude is nothing strange to ordinary literature either, of course.

To write games that are spitting at you, or teasing you to try them, or plainly have a laid-back stance to both you and itself … it is an idea that carries lots of opportunities.

Atonality

Posted By: David ArtmanDone properly, it can underscore the moments of consistency AND convey a message, via contrasting tone, with the moments of insanity

I like this. It could be very effective in a text dominated by the neutral tone of rules.

As a game text is ordinarily broken up in more or less stand-alone elements, there is no saying how far you can go with this, both in the deconstructive and constructive way …

Structure

Posted By: David ArtmanCan a LtRPG carry surprises, nestled in the sequence of presentation, just like a novel can use flashback to clarify what was, prior to the flash, a very ambiguous or downright confusing scene?

I do think so! To play around with the structure in such a text can dig up many hidden effects, I think.

I really love the idea of going for instructions “in medias res”, and then informing about what this is all about. There is vast fields for fruitful misinterpretations here! I love misguided players!

David, I believe you have made a nice overview of the main elements at play in a literary game text. And you have made some very nice and thought-provoking speculations on what kind of tools and effects to be had for the avid writer.

Thanks to your analysis I now feel even more fired up on this idea! A thousand thanks to you for making the effort!

Mind you: I am not equaling this kind of game-texts with role-playing poems. The poems are made to be played. As such they are both interesting in themselves, with their narrow timeframe, and interesting as tools for research by designers. Writing role-playing poems are a great way for designers to test specific game-tools, and a great way for them to test how their writing in general translates into games.

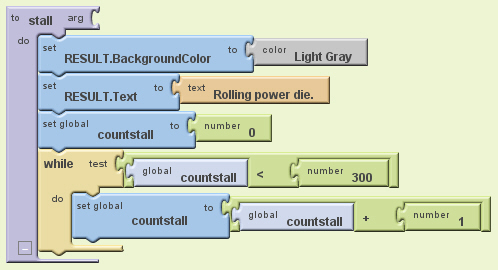

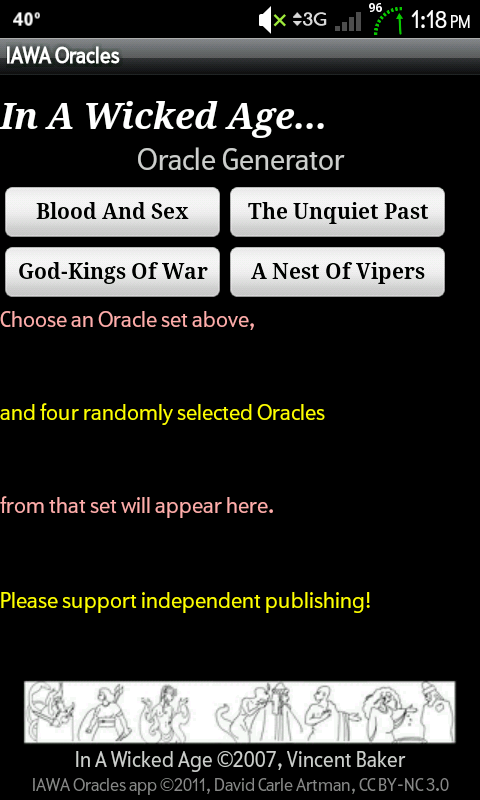

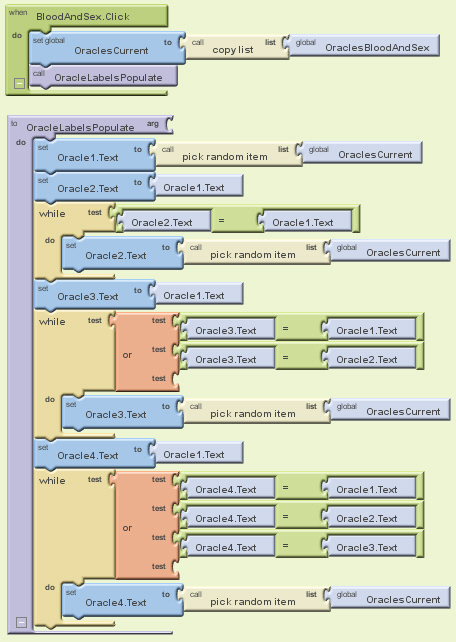

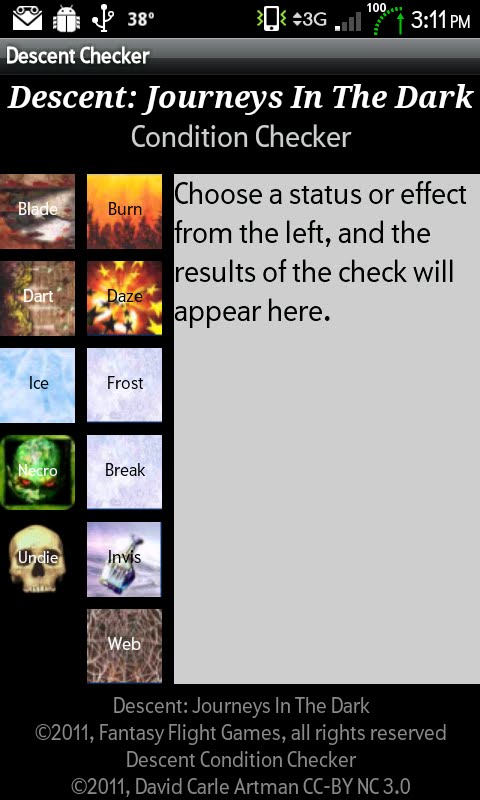

Playing Descent: Journeys In The Dark (1E) can be an exercise in confusion, especially when one has several conditions in play, is a Necromancer, and is wandering through a trapped dungeon. My second app for Android, built using App Inventor, is designed to make such checks fast and error-free.

Playing Descent: Journeys In The Dark (1E) can be an exercise in confusion, especially when one has several conditions in play, is a Necromancer, and is wandering through a trapped dungeon. My second app for Android, built using App Inventor, is designed to make such checks fast and error-free.